Silk was not even the biggest product imported from the East; pepper from India was.

William Dalrymple, Historian, 2024.

Exploring the Silk Roads in London

Introducing the Silk Roads

Where do the Silk Roads begin, and where do they end? Who “invented“ them, and when?

It is a vast subject and entire Books are dedicated to answering these big questions. Currently, two exhibitions in London are dedicated to the topic.

This text offers an introduction of the Silk Roads by examining both exhibitions and by exploring different perspectives on the concept.

From Ferdinand von Richthofen to Xi Jinping

The ancient network of trade routes called “Silk Road(s)“ is a rather modern invention. German geographer and explorer Ferdinand von Richthofen (a nephew of the famed ‚Red Baron‘) is commonly credited with having coined the term in 1877. However, a fellow German geographer, Carl Ritter, had already mentioned the term in 1838.

Von Richthofen, who spent years in China and Central Asia, published several volumes based on his research. According to Prof. Waugh from the University of Washington, von Richthofen was aware of the limitations of his concept of the Silk Roads as “Hauptstrassen“ (main roads) from East to West.

[Von Richthofen] applies it, sparingly, only to the Han period, in discussing the relationship between political expansion and trade on the one hand and geographical knowledge on the other. The term refers in the first instance to a very specific east-west overland route defined by a single source, even though he recognizes that at that time there were other routes in various directions (pp. 459-462) and at least to some extent appreciates that silk was not the only product carried along them. (Silk Roads Newsletter)

In the decades since, modern archeology has greatly expanded our understanding of these networks, providing us with evidence that human activity along these routes was far more diverse and much older. This exchange of goods and ideas is considered as an early form of globalisation – as ancient, perhaps, as human migration itself.

Despite these findings, von Richthofen’s limited definition of the ancient trade routes still resonates today.

Just a decade ago, China’s leadership revived the Silk Roads, including an updated nationalist origin story. The official starting point of this new Chinese narrative was in 2013, when President Xi Jinping announced the “Silk Road Economic Belt” and the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road”.

These “New Silk Roads“ have become known as “One Belt One Road“ (OBOR) and the “Belt and Road Initiative“ (BRI). Eleven years later, the BRI aims to be all-encompassing: On land and on water, in space, in the digital realm as well as in sectors such as health. More on this further below.

Exploring the Silk Roads from 500 AD to 1000 AD

Within this historical and contemporary context, two exhibitions in the UK‘s capital are enlightening visitors about the worlds and lives along the ancient Silk Roads. Both shows aim at offering fresh perspectives on the Silk Roads instead of looking at them as a mostly one-directional trade route from East to West.

The first exhibition, A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang is on display at the British Library. The second, simply titled Silk Roads, is at the British Museum. Both exhibitions focus on the years from 500 AD to 1000 AD, a period characterised by the spread of religions, ideas and commodities across Afro-Eurasia.

Indian Buddhism became popular in large parts of Asia. Islam was a new and powerful force rapidly gaining followers in the Arab world and beyond. Nestorians carried Christianity deep into Central and East Asia. The kingdom of Aksum, in modern-day Ethiopia, controlled the important waterways of the Red Sea connecting the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean. Civilisation blossomed in Tang China. While Europe, after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, went through “the Dark Ages“.

Silk Roads exhibitions in London – praise and criticism

Both exhibitions have received a lot of praise, with Silk Roads having received some criticism as well.

According to the Guardian, the Silk Roads exhibition is one that turns world history “upside down“. The Financial Times praises the cooperation of “several core curators, rather than a lead specialist assisted by colleagues in the same field“ as a novelty. Peter Frankopan, author of the bestseller “The Silk Roads“, describes it as a “once-in-a-lifetime show.“

The interactions and military competition between peoples such as the Türks and the Uyghurs, who also feature prominently here, were central to global history: some 85 per cent of large empires formed over the course of more than 3,000 years developed in or close to the Eurasian steppe. (Telegraph)

Then there is William Dalrymple, renowned Scottish historian and expert on India who “absolutely loved“ the A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang at the British Library. The Silk Roads exhibition at the British Museum? Not so much.

Mr. Dalrymple could not help but notice that there were only East-West maps on display at the British Library, emphasising that “you can’t understand Dunhuang unless you understand Buddhism coming out of [India].“

“A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang“ at the British Library

A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang showcases treasures from the edge of the Gobi desert in today’s Xinjiang province, China. Dunhuang was once an important stop for merchants, pilgrims and envoys alike. Their journeys could stretch as far as Constantinople in the West, Japan in the East, Scandinavia in the North or India in the South. Carrying with them and exchanging precious goods, ideas, religious beliefs and new technologies.

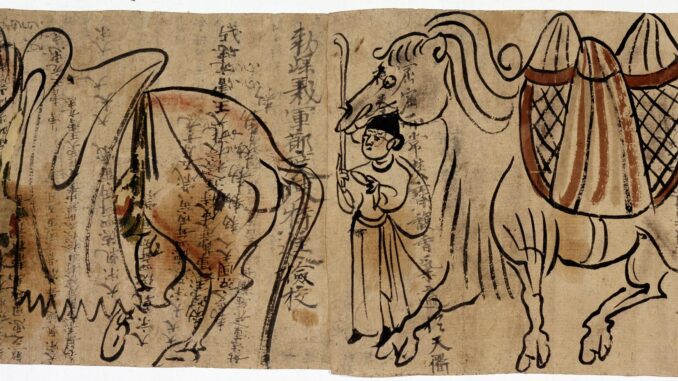

The relics discovered in the nearby Buddhist cave complex of Mogao offer valuable glimpses into our common past. The exhibition presents manuscripts, artwork and documents found inside the Library Cave, built in the 9th Century during the Tang Dynasty. Before being rediscovered accidentally by a monk in 1900 the Library Cave had remained sealed for almost 900 years.

Highlights of the British Library’s exhibition:

- The Diamond Sutra (868 CE), the world’s earliest complete printed book with a date, and one of the most influential Mahayana sutras in East Asia

- The Dunhuang star chart, the earliest known manuscript atlas of the night sky from any civilisation

- The Old Tibetan Annals, the earliest surviving historical document in Tibetan, giving a year-by-year account of the Tibetan empire between 641 and 764

- A manuscript fragment dating from the 9th century about the prophet Zoroaster or Zarathustra, nearly 400 years older than any other surviving Zoroastrian scripture.

- The longest surviving manuscript text in the Old Turkic script, a Turkic omen text known as the Irk Bitig, or ‚Book of Omens‘ (British Library)

If you’re interested in exploring the Dunhuang caves further, the “Dunhuang Caves on the Silk Road” project and the International Dunhuang Programme are two excellent websites offering resources (links below).

“Silk Roads” at the British Museum

Crossing deserts, mountains, rivers and seas, the Silk Roads tell a story of connection between cultures and continents, centuries before the formation of the globalised world we know today. (Silk Roads – British Museum)

This view is once again challenged by Mr. Dalrymple, who criticises the Silk Roads as “misleading“ and “conceptually narrow.“ Its major fault being the “lack of any real consideration of India“ even though it was the largest trading partner of the Roman Empire.

He supports this with two main arguments. First, sea travel was superior to land routes because of the monsoon winds. Second, the lack of “any free movement of goods between China and the West at any point before the Mongol period in the thirteenth century.”

In his new book “The Golden Circle” Mr. Dalrymple argues that the notion of the so-called Silk Road, an overland route linking China with the Mediterranean from East to West, is a myth. Like other critical voices he sees the root of this myth in the late 19th century. Today, this myth was nurtured by a “Sino-centric reframing of history.” The book’s publication around the time of the two exhibitions’ openings was either a funny coincidence or good strategic marketing.

The role (or lack) of the “Indosphere“ and its influence is exemplary for discussions relating to questions of how inclusive or exclusive the Silk Roads had been in the past and their interpretations today.

500 years and 300 objects in about 90 minutes

Your author had the chance to visit the Silk Roads special exhibition at the British Museum in London and found enough room for both praise and criticism.

Once inside the dimly lit gallery, the journey with about 300 objects arranged along 15 trading hubs begins. In contrast to the noisy hustle and bustle of the main halls, there is a pleasant and almost devout silence inside the small gallery space.

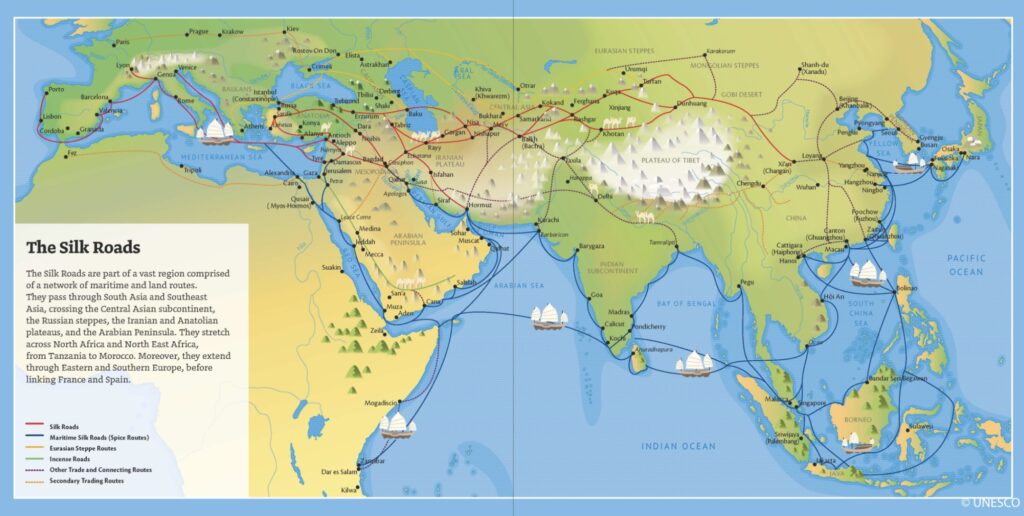

An installation projected to a wall by the entrance sets the conceptual framework. Dots and lines highlight that this was not simply a one-directional route from East to West, but rather an interconnected network spanning across Afro-Eurasia. Not just one main overland route bringing silk from East to West, but many routes on land and on water.

From East Asia to Western Europe

One of the first objects to marvel at is a small seated Buddha statue that intends to underline this understanding of the Silk Roads. This beautifully crafted piece of copper was probably made around AD 500-600 in the Swat valley, Pakistan. It was excavated in a medieval settlement on a Swedish Island.

The gallery space is packed with mesmerizing treasures. Like a Sogdian wall painting from the ancient palace of Afrasiab in modern Uzbekistan, on loan from the Samarkand State Museum. The scenes in the “Hall of Ambassadors” originally covered four walls, depicting the multi-directional and cultural diversity of the times.

[W]hat is clear is that the pictorial program was meant to represent the reach and power of the ruler of the most important Sogdian city-state—ironically, on the eve of the Arab incursions into Sogdiana. (National Museum of Asian Art)

Another masterpiece is this 1533 manuscript of the original map by al-Idrisi from 1154. The map depicts the known world, with Mecca in the centre of medieval Arabic geography.

These are just three examples of many found along the routes from Korea to England. You can explore the exhibition and more of its highlights, like the world’s oldest group of chess pieces, on the British Museum’s website.

“Silk Roads“ is a great show..

For anyone with an interest in the topic, visiting the two exhibitions is a great joy. Both exhibitions are on display until 23 February 2025. The curators and the team involved made an effort in putting the objects in the spotlight and letting them speak for themselves. An unobtrusive sound installation in the background is accompanied by a few projections of silk road landscapes on the walls. This atmosphere can take a visitor out of Bloomsbury to Samarkand or another of the 15 featured trading hubs. An Audio guide provides exclusive curators’ commentary on a selection of highlighted objects.

It is an impressive journey. However, more visualisations about the different peoples and their lives could have enlivened these bygone ages even more. The curators might have limited such extras deliberately in order to keep the focus on the objects themselves. Because of the dimensions of time and space, spanning over centuries and continents, one could find the exhibition too confined and packed. A larger exhibition space might have added to the experience. The crucial role of the “Indosphere“ and other influential actors might get more prominence in a larger setting.

…but a rather exclusive one

The biggest issue are the ticket prices which start at 22 Pounds. This makes Silk Roads a rather exclusive event.

Its biggest achievement might be the explicit effort of debunking any myths, narratives or claims regarding the Silk Roads. It successfully illustrates that there was no single route or country of origin. Making a point in not politicising the topic is another important characteristic.

Which brings us to the Chinese view of things.

Plurality and Diversity vs. the Chinese Narrative

Silk Roads has a slightly different title in Chinese. It is called “八方丝路:万里共风华“ (Silk Roads in all directions: thousands of miles of magnificence). Again, it is emphasised that there was not just one main route but many pointing in all directions – like the needle of a compass. The Chinese language introduction concludes in bold letters:

It shows us an interconnected world of people, objects and ideas.

Both Silk Roads exhibitions in London counter the Chinese narrative with its origin story. It is one that is going back more than 2000 years. According to it, an official during the Han Dynasty under emperor Han Wudi explored the so-called Western Regions. The official’s name is Zhang Qian and he “opened up the Silk Road.” Hence, these “pioneering journeys” in 138 BC and 119 BC mark the official establishment of the Silk Roads.

A typical version of this narrative can be found on the website of the China Silk Museum. A text from an exhibition in 2020 lets visitors

review the long historical background of the Silk Roads and thus deepen their understanding of the profound cultural foundation of the Belt and Road Initiative.

From Han Wudi to Xi Jinping

In this narrative, past and present have become one since Xi Jinping announced the New Silk Roads and the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013. The Silk Roads are framed as China’s “most globally influential and open cultural heritage.“

Since 2014, “Silk Roads: The Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor” jointly presented by China, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan is on the World Heritage List.

One main slogan of Chinese interpretation of the Silk Roads is to “embody the core spirit of peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning, and mutual benefit.” According to critics, it is instead characterised by ownership and the claim of being its sole intellectual proprietor. In comparison to the message that both exhibitions in London convey, the Chinese efforts are described by some scholars as an attempt to rewrite world history.

This problematic claim becomes obvious when reading “The Belt and Road Initiative: A Key Pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future,“ a white paper published by the State Council on the occasion of the BRI‘s 10th anniversary. Both the chronology and the message are familiar:

Over two millennia ago, inspired by a sincere wish for friendship, our ancestors traveled across grasslands and deserts to create a land Silk Road connecting Asia, Europe and Africa, leading the world into an era of extensive cultural exchanges. More than 1,000 years ago, our ancestors set sail and braved the waves to open a maritime Silk Road linking the East and the West, beginning a new phase of closer communication among peoples.

What is always missing are the peoples who had already been there. Nomadic tribes in Central Asia such as the Xiongnu, the Sogdians and others had already been using these established trade routes long before any Chinese “pioneering journeys.” Not to mention the Mongols. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Pax Mongolica dominated and profoundly shaped life and trade along the Silk Roads.

China at the sole center of the ancient Silk Road?

The Chinese governments official Belt and Road Portal website has one article about the Silk Roads exhibition at the British Museum. It is another example for how resolute and unwavering information is selected and incorporated into what the Party wants it to be. The following supposedly is a quote by Luk Yu-Ping, chief curator of Silk Roads:

According to Lu Yuping, the exhibition’s chief curator and a researcher in the British Museum’s Asia Department, China was at the center of the ancient Silk Road, not only in terms of economic development but also in terms of cultural exchanges and the spread of technology and ideas.

本次展览主策展人、大英博物馆亚洲部研究员陆于平认为,中国在古丝绸之路中处于中心地位,这不仅体现在经济发展,还体现在文化交流、技术和思想传播.

The spelling of Ms. Luk’s name in Mandarin as “Lu” instead of her Cantonese name “Luk” is a small detail showing the policy of Sinicisation according to the Party. Let’s compare this quote with what Dr. Luk says about Silk Roads elsewhere:

One of the biggest challenges at first was to define a concept as broad as the “Silk Roads”, but luckily, we soon came to an agreement. The Silk Roads, as we define it, is a history of connections, and the exploration of the movements of people, objects, and ideas. (Huo Family Foundation)

One last quote from the British Museum‘s Chinese language blog:

In the hundred years or so since the term appeared, research on the Silk Road has gradually revealed a richer and more intricately connected world. The Silk Road journeys covered a much wider territory than first thought. (British Museum)

Music, uniting feature throughout the ages

This text has presented different perspectives and discussions regarding the Silk Roads in general and the two current exhibitions in particular. On the one hand, it demonstrates the difficulties of doing justice to all the parties involved across time and space. On the other, it shows how perspectives are still biased and exclusive, regardless if they are Euro-centric or Sino-centric.

Fascinated by the topic but not able to be in London until February next year? Alternatively, the Humboldt Forum in Berlin has an entire section dedicated to the “Northern Silk Road”. The exhibition is permanent and admission is free.

Let’s end this article about the Silk Roads with something less political and less dividing. Instead, let’s focus on one uniting element that has been present across time and space: music!

In 1998, Korean-American Cellist Yo-Yo Ma founded the Silk Road Project in order to bring together musicians. Listen to the latest album here:

#109 „China’s hidden century“ Ausstellung zur Qing-Dynastie

More on the Silk Roads/Sources

ARTNET: British Museum’s Splashy New Show on the Silk Road Meets With Controversy

BBC4: India past and present

BRITISHMUSEUM: Silk Roads

BELT AND ROAD PORTAL: https://www.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/0IITPOQ1.html.

BELT AND ROAD FORUM: http://www.beltandroadforum.org/english/n101/2023/1010/c124-895.html.

CHINASILKMUSEUM: https://www.chinasilkmuseum.com/index_en.aspx.

DUNHUANGPROJECTS:

Dunhuang Caves on the Silk Road

International Dunhuang Project

GETTY: Peter Frankopan on the Silk Roads

HÖLLMANN, THOMAS O.: China und die Seidenstrasse, C.H. Beck (2022).

HUMBOLDTFORUM: Cave of the Ring-Bearing Doves

SILKROADFOUNDATION: Richthofen’s Silk Roads

TIMESOFINDIA: Dalrymple criticises British Musuem exhibition ‚Silk Roads‘

UNESCO: Silk Roads Programm

Antworten