As your envoy can see with his own eyes, we own everything. I attach no importance to objects that are foreign or inventive, and I have no use for your country’s production.

Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) to the British King George III, 1793.

China and the Qing Dynasty: “China’s hidden century” at the British Museum

After four years of preparation and a collaboration of 100 scientists from 14 countries, the British Museum in London presented a special exhibition on China. From May 28 to October 8, visitors could marvel at more than 300 exhibits as part of “China’s hidden century”.

Sinoskop went to see the exhibition and did enjoy the objects on display with many other – mostly Chinese speaking – museum visitors.

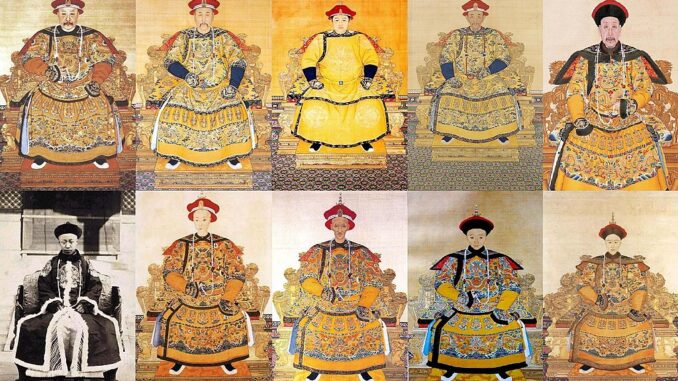

Some context: The Ming (1368-1644) were followed by the Qing. China’s last imperial dynasty ruled from 1644 to 1912. Originating in the northeast, the founders of the Qing themselves were not Han Chinese, but Manchus, a nomadic people from Manchuria.

Emperor Qianlong abdicated in 1796 after 60 years on the throne, and was succeeded by one of his sons who became the Jiaqing emperor. A long period of stability was followed by instability. The final years of the 18th century marked the beginning of the end of the Qing and the Chinese imperial system as a whole. With the abdication of the last emperor Xuantong (Puyi) in 1912, China’s so-called “long century” came to an end.

The 250-year rule of the Manchus was a period marked by imperial rise and revolutionary decline.

“China’s hidden century“ at the British Museum (1796-1912)

This period of violence and turmoil was also one of extraordinary creativity, driven by political, cultural and technological change. In the shadow of these events lie stories of remarkable individuals – at court, in armies, in booming cosmopolitan cities and on the global stage. (Website British Museum)

Entering a rather small, dark room with a single illuminated display case in its center is where the journey begins. Inside the case, an elaborate map made around 1800. Painted in blue ink on eight long scrolls of paper the Chinese Empire presents itself in all it’s greatness.

The “Complete Map of All Under Heaven Unified by the Great Qing“ was to be the first treasure of many more to come (link for digital images of some exhibits below).

The Manchus extended their sphere of power to the border regions in the north, the south, Taiwan, Tibet and East Turkestan (Xinjiang). On the map, Europe is visible far off at the edges. Within a little more than a century, China reached its greatest historical extent under the Qing in 1759. By 1796, the Qing ruled over a third of humanity and created one of the most prosperous empires in world history, according to an information panel.

A few display cases further, a nearly 600-page strong dictionary illustrates how this enormous and diverse empire was governed. State and society of the Qing dynasty were multiethnic and multilingual in character: Manchu, Tibetan, Mongolian, Uighur and Chinese were all official languages.

宫廷 / “Court“

Six Qing emperors ruled between 1796-1912: Jiaqing, Daoguang, Xianfeng, Tongzhi, Guangxu, Puyi. And one “shadow empress” , Cixi:

Three adults were followed by three children, whose reigns were dominated by Empress Dowager Cixi. (British Museum BM)

The exhibition‘s curators emphasise the role of women during China’s “long“ or “hidden“ century. Without doubt, no woman stands out as an exceptional personality as Empress Dowager Cixi. From 1861 to 1908, the former concubine of the Xianfeng Emperor and mother of the Tongzhi Emperor held state power for almost half a century.

Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

“China’s hidden century“ – exhibition at the British Museum

Some audio recordings are also part of the exhibition experience and available online: Here a trilingual recording of Cixi’s words about her own life and comparisons with her contemporary in the United Kingdom, Queen Victoria.

Among the items on display here is a magnificent informal robe, of which Cixi is said to have owned hundreds and changed them a good ten times a day. Phoenixes and peacock eyes shine here in the most splendid colors, inspired by Japanese kimono motifs of the Meji period.

Note: In the People’s Republic of China in 2023, wearing such “foreign-inspired” clothing could have negative consequences for the wearer. A new law aims at criminalising clothing that is “harmful to the spirit” or “hurts the feelings of the Chinese people.”

Also on display, precious objects of everyday life and ritual use made of glass and porcelain, metal or silk. Evidence of how splendid and artistic imperial court life of the Qing must have been.

The life of the dancer and diplomat’s daughter Yu Rongling is highlighted as another remarkable personality. After stays in Japan and France, she was the first to bring Western dances to the imperial court and Yu Rongling is therefore considered “China’s first modern dancer”.

武威 / “Military“

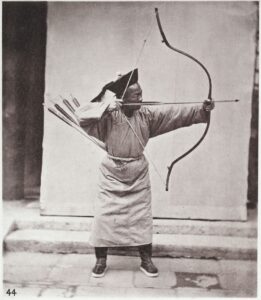

The basis of Qing rule was a well-organized military apparatus which was divided into the so-called “eight banners”, composed mainly of Manchus, Mongols and Chinese.

The military section offers, various uniforms, some of which are enormous, land and sea maps, as well as drawings and sketches of military exercises.

Recording of General Mingliang, who served under emperor Qianlong.

Manchu rule came under increasing pressure. Continuous rebellions, such as the “White Lotus,” a religious sect, Muslim uprisings in East Turkestan (Xinjiang) and other parts of the empire, as well as the Taiping Rebellion all challenged Qing power and exhausted resources.

Above all, the conflicts with foreign invading powers led to a series of devastating defeats for imperial China. The Opium wars, the Sino-French War, the Sino-Japanese War, and the Boxer Rebellion exacerbated a period of permanent crisis.

The remaining part of the section is dedicated to the two Opium Wars, the destruction of the Summer Palace by Western troops and the Taiping Rebellion. Behind glass you can see the first of the so-called “unequal treaties” between China and the imperial powers. The Treaty of Nanjing, signed in 1842 between the Qing and Britain, represents the beginning of the forced opening up of China.

Remains of the Summer Palace in Beijing, built during the Ming Dynasty and destroyed in 1860, symbolize this era of glory and decline.

The brick and stone ruins of European-inspired buildings have become the defining symbol of European violence against 19th century China. (BM)

As another extraordinary personality of “China’s hidden century”, the life of Hong Xiuquan (1814-1864) cannot be left unmentioned. The former village teacher and failed civil servant came into contact with Christian teachings through missionaries in China.

After having suffered from a nervous breakdown, young Mr. Hong was convinced that he himself was the younger brother of Jesus Christ. He thus appointed himself ruler of the Taiping Tianguo, the “heavenly kingdom of eternal peace”.

In the mid-19th century, the Taiping made Nanjing their capital, and it would take more than a decade and some 20-30 million lives to put an end to the Taiping rebellion.

This section illustrates well how the period was characterized by the simultaneity and multiplicity of internal and external conflicts. The military conquests, campaigns, conflicts and defeats all contributed to the rise and fall of the Qing.

文薈 / „Artists“

Although the Qing faced enormous internal and external pressure and violence in the 19th century, art in China still flourished in “coexistence” with new “modern” art from the West.

Highlighted is the artist Ren Xiong, who died of tuberculosis in 1857 at the age of only 34. His self-portrait of 1851 is considered “the most extraordinary in the history of classical Chinese art,” explains the accompanying text.

Recording of the characters next to Ren Xiong’s self-Portrait in Chinese and English.

Many contemporary artists sought inspiration in the past and found it in classical calligraphy. Calligraphy and poetry created by women also gained more recognition.

Printing presses ran hot and a heyday for books, magazines and newspapers began. These became part of a new everyday culture in the big cities on the coast, particularly in Shanghai. The accompanying emergence of public opinion in urban centers became another nail in the coffin for the monarchy. Calls for modernization, as well as for a national identity that was not Manchu but “purely” Han, grew louder.

風尚 / “Everyday life“

In the mid-19th century, in the midst of conflicts and natural disasters, the population of China grew rapidly to about 450 million people. 90% of them lived in poor conditions, and life expectancy was only about 40 years. Many people were drawn to the newly industrializing cities, where, in addition to new opportunities, a new class emerged that achieved considerable prosperity through trade and entrepreneurship.

Despite these struggles, cities developed rapidly as displaced but resilient people emigrated in search of security, work and food. (BM)

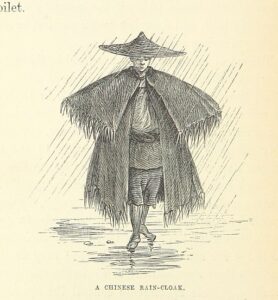

A number of showcases here are filled with clothing of the wealthy; fine robes and little shoes made of velvet and silk, delicate hair ornaments. However, one can also glimpse at those of the common people. Like the work clothes of a southern Chinese street cleaner in the rain. For centuries, farmers, fishermen, etc. wore such a raincoat woven from straw and the matching hat.

交流 / “Global Qing“

In the last 60 years of Qing rule, modern technologies and transportation revolutionized industry and changed people’s lives. (BM)

As an outstanding personality of the “global Qing”, the merchant Mouqua smiles mildly at the beholder from an oil painting. Mouqua was the head of the “Hong”, a merchant guild in Canton (Guangzhou), who were the only ones allowed to trade with foreigners at the beginning of the 19th century.

A recording about Mister Mouqua‘s life.

Here, visitors are being introduced to yet another extraordinary woman. As the adopted daughter of an American missionary, Ida Khan studied medicine in the USA and England and returned to China at the end of the 19th century. She was considered a “modern woman” who stood up for women’s rights.

Again and again during the tour it becomes clear how (Western) modernity entered all areas of Chinese life. Foreign influences were adopted and very often new styles and developments emerged.

At the same time, resistance to these influences grew and brutal incidents occurred. Chinese popular anger against Christian missionaries erupted in the port city of Tianjin (1870) – seen on a contemporary fan decorated with a burning church, on the Yangtze River (1891), and during the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901).

世變 / “Reform to Revolution”

In the last section, the visitor also approaches the end of a 2000-year-old ruling system. The defeat in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) revealed the military backwardness of the Qing dynasty and made far-reaching reform efforts inevitable. Whether in the military, education, administration, or the Qing’s relations with the rest of the world, demands grew louder for the state and society to be reformed and modernised following a Western model.

A group of intellectuals wanted to radically implement the necessary change with the so-called “100-day reform”. However, this radical approach was prevented by conservative circles at the imperial court. Among the best known of the reformers were Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao.

A few years later, in 1905, the traditional, Confucian-influenced examination system was finally abolished and the first universities were founded.

Li Hongzhang was another outstanding and influential character. As a diplomat, he represented the Qing at the coronation of the Russian Tsar Nicholas, met the English Queen Victoria, Otto von Bismarck, and the German Emperor Wilhelm II. As a military, he commanded the most modern army in northern China.

Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

However, reformers and revolutionaries were divided on what the future of a modern China should look like. For both, Japan had become a common role model, and its neighbor attracted many young men and women.

Intellectual reformers looked to Japan because it had modernized while retaining the emperor. Revolutionaries also drew inspiration from Japan, but they wanted to overthrow Qing rule. (BM)

The last outstanding person to be introduced is Qiu Jin, a feminist, poet and revolutionary. She was executed by beheading in 1907 at the age of 31. At the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, Qiu Jin was revered as a great martyr of the revolutionary movement.

As a transitional figure between the Qing Empire and the modern world, she is still a celebrated figure in China today. (BM)

The final audio file is a text about Qiu Jins life.

Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“China’s hidden century“ 1796-1912

Visiting the British Museum and it’s regular exhibition on China is never wasted time, but always offers the opportunity to travel back in time. The special exhibition “China’s hidden century” set its focus on the last century of the empire, its decline and the birth of modern China. This eventful period still reverberates today.

Then as now, China’s role in the world was and is characterized by phrases such as “national question”, “century of humiliation”, “territorial claims”. The potential for conflict associated with such phrases is still being disputed and negotiated in the early 21st century. That “China’s door is opening wider and wider,” as the Communist Party’s propaganda nowadays mantra-like emphasizes, is just one part of the historical legacy of China’s “long” or “hidden century.”

More on the topic

BRITISHMUSEUM: China’s hidden century

The British Museum website has digitised some exhibits, as well as other related resources.

ARTE: The first of three parts of the Arte documentary “The History of China” tells of the decline of the Qing and shows the “Fall of a Dynasty (1839-1908)” with historical

BBC: The Story of China – BBC Doku von 2016

Antworten